indicator

Silla Clay Dolls (Tou) – a glimpse into the culture of ancient Koreans

These boldly made clay human and animal figurines are stunning symbols of the intricate beliefs of ancient Koreans.

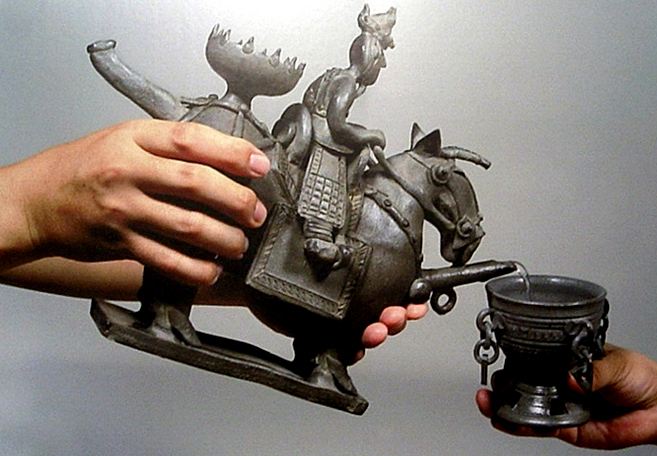

<A horse and rider-shaped clay teapot found at the Geumryongchong Tomb from the Silla Kingdom, 6th Century.>

<A photo showing how the teapot was likely used.>

Tou, the fruit of the desire to live even after death

Human desire has no end. The more it is satiated, the larger it grows. An extreme example of such human desire is the practice of burying the living with the dead (called "sunjang" in Korean). Due to the desire to take the material prosperity enjoyed during life into the afterlife, not only objects and horses owned during one's lifetime but even people closest to the deceased were brought along. The practice of sunjang is found in many places throughout the world. In Korea, it was widely practiced until the Three Kingdoms Period (57 B.C.-668 A.D.), with human bodies and burial accessories often found in the tombs of the Gaya and Silla Kingdoms.

<King Michu's tomb located on the outskirts of Gyeongju in a kofun at Hwangnam-ri was the site where countless tou and tou-decorated earthenware items were found in 1926.>

With developments in civilization paired with increased ethical awareness, the practice of sunjang gradually declined and was eventually abolished. With the abolishment of sunjang, the people and animals buried with the deceased came to be replaced by substitute figurines. The Silla people made these figurines out of clay (called "tou" in Korean). The word "tou" literally means "doll made out of clay." Tou were made not only of human figures but also of various types of animals, everyday items and homes. These types of figurines are common in both Western and Eastern cultures and have similar goals and functions; their use for shamanic or incantation purposes or as grave items was particularly important in the East.

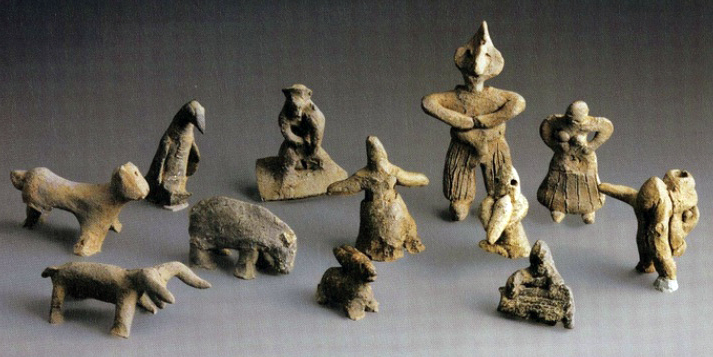

<A variety of Silla clay dolls.>

A 1,500-year-old clay snapshot: the life, death and sexuality of the Silla people

One special feature of the Silla tou is that male and female sexual organs are made intentionally large, while sexual acts between men and women are also boldly depicted. As well, the range of subjects is fairly wide, including animals like turtles, ducks, horses, frogs and snakes. Each tou is like a snapshot of the everyday lives and hopes of the Silla people—one that has transcended 1,500 years to come to us today.

<A clay doll in which the male sex organ has been humorously emphasized (left) and a Silla clay doll of a woman giving birth (right).>

The reason for the enlarged representation of male and female sexual organs is the hope for fertility and abundance. In ancient societies, sex indicated procreation. The practice of a man and woman enjoying one another physically in a field freshly sown with barley seeds remained until well into the 19th century. The practice was based on shared hopes for a plentiful harvest. This was also the reason for emphasizing the breasts or buttocks, or pregnant bellies of female tou.

<Clay dolls depicting sexual activity (left) and childbirth (right).>

The snake and frog were symbols of regeneration and a long, energetic life. In other words, they symbolized eternal life. Just as the snake casts off its skin and is then reborn, people wanted to be able to cast off the "obligation" of death to enjoy eternal life. The frog was interpreted using the same logic. By waking up after a long winter's sleep, the frog was believed to be reborn after undergoing the process of dying through hibernation.

<A clay lid of jar ornamented with clay figures of snake, turtle, frog, fish.>

In Eastern tradition, the turtle is a sacred animal representative of longevity. It embodies the hope for eternal life that both those in the present world and in the afterlife desire. In the East the turtle, as well as occasionally the bird or duck, acts as a mediator between human beings and the gods. Ancient Koreans believed that there was a wide river between this life and the afterlife. The dead had to cross this river to continue to the afterlife. Tou of birds and ducks were created due to their important function in carrying people from this life to the afterlife.

<A duck clay doll of Silla housed in National Museum of Korea.>

There are many types of tou symbolic of regeneration and abundance in the afterlife. The Silla people wanted to leave many descendants, live eternally like the snake and frog, and safely cross the river into the afterlife on the duck's back. In this way, tou are vital for understanding the Silla people's vision of the universe and their philosophy on life and death. Also, the realistic appearances of tou are invaluable resources for learning about the lifestyle and society of the Silla people.

The bold and lively beauty of Silla clay dolls

Silla clay dolls are characterized by an absence of fine detail, with their highly simplified appearance making them look as though they were made with a single hand movement. While they ignore conventional rules of proportion and often lack details, certain parts are boldly emphasized to bring attention to their symbolic significance. These parts are telling indications of what the Silla people believed to be important, as can be seen in the sexual acts between men and women and the depictions of sexual organs. The desire of this agrarian society for the prosperity of one's offspring and abundant harvests is evident.

<An earthenware pot excavated from a Silla tomb is adorned with many clay figures, including animals and people engaged in sexual activity.>

Many Silla tou, even those with sad facial expressions, were made to bring about laughter rather than sadness. When considering that tou were originally made as grave objects for the deceased, this is a representation of the Korean cultural desire to overcome even death and pain with humor. The tou of Silla reject all artificial expressions and imaginary depictions of everyday life, and are crude but honest depictions of human instincts and emotions.

<A smiling elderly man and a woman mourning over the dead.>

* Photos courtesy of National Museum of Korea and Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea.