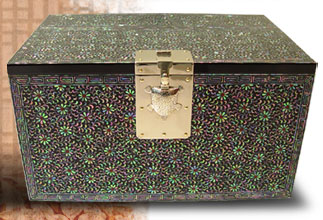

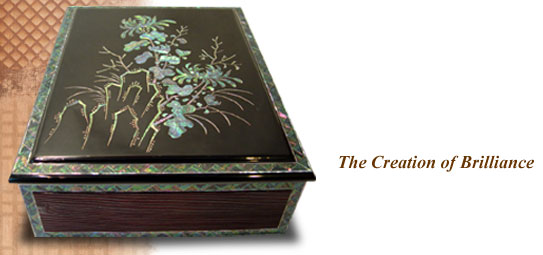

The painful decade of apprenticeship began to pay off as his reputation grew along with his income. By this point, he decided to raise the level of his wood lacquer work from producing house wares to creating lacquer art. Another learning process ensued, during which he made extensive tours to museums and galleries across the country to learn from surviving masterpieces of Najeon Chilgi. He also read countless art books to study the forms, colors, patterns and techniques, and made numerous experiments in his wood lacquer workshop to create his own style. His 30s were spent this way. Najeon Chilgi is often called a comprehensive art as it involves a number of crafts including woodwork and metalwork, in addition to making mother of pearl strips. Therefore, a craftsman must spend many years studying Najeon Chilgi as well as to be proficient in many other different crafts. When Song Bang-ung was in his 40s, he began entering national craft shows and competitions and gained a nationwide reputation as an exemplary craftsman. He received several prizes and awards, including the President’s Prize, the highest honor any artist can get in a national arts and crafts competition in Korea. However, his most special award was the Culture Minister’s Prize at the 1981 National Folk Craft Show; 1981 was the year his father passed away and he felt the award honored the man who taught him everything he knew. In 1990, on the other hand, use thicker strips from various shells to inlay into wooden objects, while Japanese craftsmen consider the mother of pearl inlaying as a subsidiary part of the Makie Kobako art. Many believe Najeon Chilgi is unique not only because the Korean artisans have mastered the technique to extract the brilliant iridescence from the abalone shell, but also because they have used the resplendent colors of the mother of pearl to their fullest extent to create such exquisite designs. Another key element of Najeon Chilgi is lacquering. Archaeological evidence proves that the use of the lacquer paint in Korea dates back to the Bronze Age, and by the time Korea was in the Three Kingdoms Period (57 B.C.-668 A.D., the period when the three ancient Korean kingdoms, Koguryo, Baekje and Silla, rivaled each other) lacquerware making had become a national importance. In the Silla Kingdom, for example, a special government agency was set up to control the production of lacquerware. In the Goryeo and Joseon dynasties, planting ‘lacquer trees’ and managing ‘lacquer forests’ was an important duty of the central government. Koreans were attracted to lacquerware because of its glossy beauty as well as its practicality for being strong, watertight and antibacterial. As some archaeological artifacts prove, a well-made piece of lacquer art can maintain its original condition for more than 2000 years. View the master's works |

||||||||||||

|