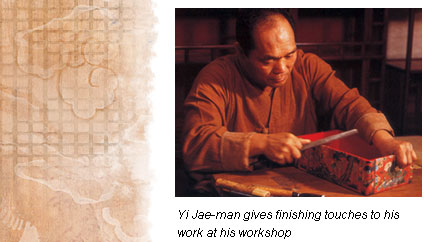

In 1968 another experience, this time a fortunate one, changed his life forever when one of his middle-school friends, who admired his artistic talent, brought him to the workshop of Eum Il-cheon. As mentioned above, Eum at the time was the greatest Hwagak artist in Korea, and who continued his family tradition of three generations. During their first visit, Eum gave Yi 50 ox-horn sheets and told the junior to bring the sheets back within a week with whatever designs he preferred to paint on them. Yi returned with his creations just after three days. Marveled at what the teenage boy had produced, Eum suggested that the boy become his pupil, but Yi declined the proposal. The senior didn’t give up and visited Yi’s house to persuade his mother that her son’s outstanding talents would make the boy a great artisan under his tutelage and guidance. She was interested in the old master’s proposition, believing that it would bring a great opportunity for her boy to overcome his impairment and find a ‘proper’ job in the future. During the following persuasion session, led by his mother this time, 16-year-old Yi Jae-man finally said yes. The toilsome life of “farming by day and studying by night,” translated from a Korean proverb, continued for most of Yi’s middle and high school days. During this time he learned Hwagak skills at Master Eum’s workshop, which was quite a distance from his house, until late at night while going to school during the day. After graduating from high school, he began to live with his tutor at his workshop and received apprenticeship training. His education was not limited to just Hwagak, but was extended to other traditional crafts such as mother-of-pearl inlaying and metal craft, of which Eum was also an expert, when Hwagak materials became hard to get. At the workshop, Yi focused all his energy on one technique at a time as if to compete against his tutor and win. By the time he opened his own workshop after successfully completing his apprenticeship, he had already became a great craftsman who had mastered the entire process and techniques of Hwagak art, from making baekgol (‘bare frames’) and jangseok (‘metal ornaments’) to lacquering. to Yi, abandoning Hwagak would be morally wrong, especially since his aged tutor had done everything he could to pass all his knowledge and skills onto him, in spite of unfavorable conditions. Yi still firmly believes that it is his moral obligation as a head pupil to uphold the wisdom and talent that his tutor bequeathed unto him. However, he did not follow his mentor’s training rigidly. As any great pupil throughout human history, he has tried to move one step further ahead of his instructor by developing new techniques, designs, colors and materials. For example, he bravely gave up the use of traditional ‘fish glue’ to adopt a chemical glue, after finding that the latter resulted in increased durability for his Hwagak artworks. He also discovered an innovative technique with which he can now produce ‘ox-horn papers’ as thin as 0.3mm. The new, sheer papers are easier to handle, adhere better and are more transparent. His magnificent achievements in the art of Hwagak, especially considering the difficulties he endured including his impaired hands, were eventually publicly recognized when in 1996 the Korean government gave him the honorary title of Master Craftsman of Ox-horn Inlaying, a traditional craft designated as ‘Important Intangible Cultural Property No. 109.’ The life of Yi Jae-man hasn’t changed very much since he received his honorable title as he still devotes much of his time to create what is new from what is old. For him, knowledge of tradition is meaningful only when it is beneficially used for creating contemporary works, and that making the same old object that his tutor made before him lacks significance. Yi believes that artisans of the 21st century should be different from those of the 20th century, and artists in the next hundred years should be dissimilar from him. He is firm that artists of each period should leave their own mark on traditional works of art for coming generations. It is in this sense that people call him a progressive artisan who loves challenge, change and development. View the master's works |

|||||||||||

|