A wonderful piece of Asian style furniture made by Master Seol begins with his outstanding ability A wonderful piece of Asian style furniture made by Master Seol begins with his outstanding ability

of finding the right wood and his knowledge of how to use it. When he sees a tree standing before him,

of finding the right wood and his knowledge of how to use it. When he sees a tree standing before him,

his intuition instantly tells him what he should do with it and how the grain of its wood would look. He

his intuition instantly tells him what he should do with it and how the grain of its wood would look. He

feels that he establishes a close rapport with a tree through the grain of its wood, which, he considers, feels that he establishes a close rapport with a tree through the grain of its wood, which, he considers,

is the meditation of the tree while it was rooted in the same spot for several hundred years. is the meditation of the tree while it was rooted in the same spot for several hundred years.

Whilst he is creating a work of art, he gains inspiration by his relationship with the tree and the

Whilst he is creating a work of art, he gains inspiration by his relationship with the tree and the

function of the furniture he is making. In fact, once a wood is chosen, he brings it to his bedroom

function of the furniture he is making. In fact, once a wood is chosen, he brings it to his bedroom

and sleeps with it. He says there is a significant difference between the works made of the wood

and sleeps with it. He says there is a significant difference between the works made of the wood

he has slept with and that of wood he hasn't. You can, he argues, find the most suited function for

he has slept with and that of wood he hasn't. You can, he argues, find the most suited function for

the wood only after you have heard its voice and know its mind.

the wood only after you have heard its voice and know its mind.

The first step to making a superb piece of Asian style furniture is to find the right wood. Quality The first step to making a superb piece of Asian style furniture is to find the right wood. Quality

wood is usually found from trees that are at least 300 years old. The older the tree, the more beautiful

wood is usually found from trees that are at least 300 years old. The older the tree, the more beautiful

the grain of its wood, and the more firm. Wood from a young tree is inferior to wood from an older

the grain of its wood, and the more firm. Wood from a young tree is inferior to wood from an older

tree in terms of patterns and hardness, plus it can easily warp. The ensuing step is to cut the tree.

tree in terms of patterns and hardness, plus it can easily warp. The ensuing step is to cut the tree.

The ideal period for cutting is between October and March because trees harvested during this period

The ideal period for cutting is between October and March because trees harvested during this period

do not have much sap and thus, do not easily decay.

do not have much sap and thus, do not easily decay.

Next, the tree must be dried in the open air for approximately five to seven years without cutting. This period of time,

during which the trees suffer the onslaught of the elements and the seasons, allows the carpenter to find excellent

wood that doesn't decompose or warp after it is made into furniture; the low-quality woods, thus, are discarded. Also,

wood that is cut before it is properly dried often results in distortion, which makes the task of Asian style furniture-making

very difficult.

When cutting the wood into sections according to their specific uses, the carpenter must take his utmost care to

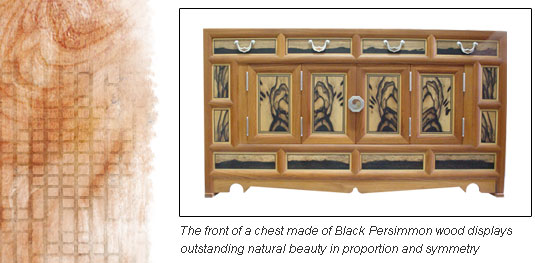

keep the beauty of the natural wood patterns. For Black Persimmon wood, for instance, the cutting process is

particularly important because the wood is usually used for the furniture's front panels so that the pure exquisiteness of

its distinctive patterns can be viewed by the beholder. Accordingly, the craftsman needs years of experience and

exceptional skills. After cutting, the individual pieces need to be dried for another three to five years in a shaded area

with good air circulation. Drying in this environment is also important to prevent the wood from warping.

This drying process is followed by a 'design- This drying process is followed by a 'design-

cutting' procedure, in which the carpenter

cutting' procedure, in which the carpenter

chooses, prior to cutting, natural patterns

chooses, prior to cutting, natural patterns

within the dried wood according to the

within the dried wood according to the

furniture's intended use. If he finds a design

furniture's intended use. If he finds a design

particularly attractive, he can cut the wood from

particularly attractive, he can cut the wood from

side to side in order to get two thinner panels

side to side in order to get two thinner panels

of the same design, which he may use for the

of the same design, which he may use for the

symmetrical front panels of a chest like the one

symmetrical front panels of a chest like the one

shown left. Another drying session ensues, shown left. Another drying session ensues,

this time only lasting about a month in an area

this time only lasting about a month in an area

devoid of moisture, before the woodworker

devoid of moisture, before the woodworker

begins the unique process of ssamjil

begins the unique process of ssamjil

('covering'). The ssamjil process involves

('covering'). The ssamjil process involves

creating a single panel by gluing two panels

creating a single panel by gluing two panels

together. The key here is that one panel should together. The key here is that one panel should

be hard, warp-resistant wood while the other should possess a beautiful natural pattern. By joining the two panels,

the craftsman can procure a panel that is strong enough to withstand distortion while displaying a magnificent design.

For instance, Zelkova wood is loved by Korean furniture makers for the beauty of its patterns, but because it is very soft

wood it needs to be backed by a hard section of Paulownia in order for it to be used in a piece of furniture.

The final process of traditional furniture-making involves the

assembling of all the pre-processed parts into a complete piece

of furniture without using nails. If the use of nails is unavoidable,

pegs made of hard wood are utilized. After attaching the pieces

together, the carpenter applies an 'earth powder solution'

(a mixture of fine earth powder and water) onto the surface of the

entire work and wipes it clean before drying. Finally, camellia or

walnut oil is applied on all over the exterior surface. The application

of these oils on top of the 'earth powder solution' helps highlight the

natural beauty of the wood, which becomes even more breathtaking

as the years go by.

To make a fine piece of traditional Korean furniture one needs

patience, as the carpenter must wait many years for the wood

to dry―yet he must also wait 1000 years for a tree to be sacrificed

in order to create a work of beauty. A creation by in order to create a work of beauty. A creation by

Master Carpenter Seol Seok-cheol vividly displays wonderful Master Carpenter Seol Seok-cheol vividly displays wonderful

elegance as a result of patience, incredible skill and time-honored elegance as a result of patience, incredible skill and time-honored

tradition. His work crafts delightful harmony between tradition. His work crafts delightful harmony between

the natural colors and patterns of the wood, and reveals the natural colors and patterns of the wood, and reveals

aesthetically the essence of the philosophy behind Korean aesthetically the essence of the philosophy behind Korean

traditional furniture: one should not oppose the law of wood, or traditional furniture: one should not oppose the law of wood, or

of nature. His work upholds the serene beauty of this fine of nature. His work upholds the serene beauty of this fine

tradition into modern times and into the future, for beholders to tradition into modern times and into the future, for beholders to

enjoy for all eternity. enjoy for all eternity.

* Photo of Seol Seok-cheol by Seo Heun-kang * Photo of Seol Seok-cheol by Seo Heun-kang

** The

first paragraph is a quote from essayist Jeong Mog-il. ** The

first paragraph is a quote from essayist Jeong Mog-il.

View the master's works

|