A tree continues to breathe even when it is ‘dead,’ after it has been cut away from its roots. Each tree possesses A tree continues to breathe even when it is ‘dead,’ after it has been cut away from its roots. Each tree possesses

its own unique grain and individuality because it breathes in a way that is unlike any other; it has its own soul.

its own unique grain and individuality because it breathes in a way that is unlike any other; it has its own soul.

There is a man who reincarnates life for each tree he touches by listening to its soul and, in return, offering the

There is a man who reincarnates life for each tree he touches by listening to its soul and, in return, offering the

most magnificent metamorphosis of form he can create so that the tree’s essence may still embody a natural being.

most magnificent metamorphosis of form he can create so that the tree’s essence may still embody a natural being.

His name is Park Chan-soo, Master Wood Sculptor.

His name is Park Chan-soo, Master Wood Sculptor.

Each piece of wood has a distinctive texture; therefore, when it is carved, its spirit is also idiosyncratic. If a Buddhist Each piece of wood has a distinctive texture; therefore, when it is carved, its spirit is also idiosyncratic. If a Buddhist

wood sculptor holds a piece of hard Zelkova wood in his hands, he may want to carve it into a Diamond Guardian,

wood sculptor holds a piece of hard Zelkova wood in his hands, he may want to carve it into a Diamond Guardian,

or one of the Four Heavenly Kings because its tough and strong texture tells him so. However, if he holds a piece of

or one of the Four Heavenly Kings because its tough and strong texture tells him so. However, if he holds a piece of

soft wood, he will be inspired to shape the figure of a heavenly lady or, more likely, the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy.

soft wood, he will be inspired to shape the figure of a heavenly lady or, more likely, the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy.

Park Chan-soo has the wonderful ability to feel the soul of the wood; thus, he never tries to force the laws of

Park Chan-soo has the wonderful ability to feel the soul of the wood; thus, he never tries to force the laws of

nature and always strives to carve what the wood wants him to create. Through his intensely deep conversations

nature and always strives to carve what the wood wants him to create. Through his intensely deep conversations

with the wood, he follows its wishes and gives it a new everlasting life for thousands of years to come.

with the wood, he follows its wishes and gives it a new everlasting life for thousands of years to come.

The art of sculpting wood dates back to the prehistoric age. In Korea, jangseung, or wooden The art of sculpting wood dates back to the prehistoric age. In Korea, jangseung, or wooden

‘Village Guardians,’ are regarded as one of the earliest examples of nonfigurative art, in which ‘Village Guardians,’ are regarded as one of the earliest examples of nonfigurative art, in which

a human figure is expressed in a highly compressed form. These wooden totem poles, erected a human figure is expressed in a highly compressed form. These wooden totem poles, erected

in groups or pairs at the entrance of Buddhist temples or villages, were worshiped as village in groups or pairs at the entrance of Buddhist temples or villages, were worshiped as village

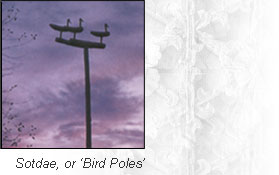

guardians and were also used as landmarks for travelers. Sotdae, long wooden poles with one or guardians and were also used as landmarks for travelers. Sotdae, long wooden poles with one or

more birds on top, were considered mediums between this world and the next, an ancient belief we can contemplate today

just by gazing at their earthly forms soaring high into the sky. In Dangun mythology (Dangun was the founder of Korea),

sotdae became a passage by which the gods descended from heaven. As they were also erected at the entrance to villages,

often alongside the jangseung, sotdae were treated as village guardians as well, although some used them according to the

feng shui belief to ‘fill what is empty’ (boheo) and for protection from evil forces and natural disasters such as fire.

The tradition of woodcarving in ancient Korean society, which was largely related with shamanistic beliefs,

entered a new, higher dimension when Buddhism was introduced to Korea during the Three Kingdoms Period

(57 B.C.-668 A.D., the period when the three ancient Korean kingdoms, Koguryo, Baekje and Silla, rivaled each other).

Many of the Buddha statues from this era were made of stone or wood, or were bronze-gilt, but

very few,

if any, wooden statues survived the subsequent wars that devastated the nation. In Korea, a sculptor of

Buddha images is called a bulmo, or ‘a mother of Buddha.’ This title signifies that the act of giving physical form to

the holy Lord Buddha not only needs exceptional carving and aesthetic skills, but also a profound religious piety,

acute wisdom and an innate responsibility.

Buddha images vary in form and style, depending on the era and country Buddha images vary in form and style, depending on the era and country

in which they were created. Buddha statues from Korea, for example, may be

in which they were created. Buddha statues from Korea, for example, may be

said to lack the qualities that inspire awe and fear: large size, majestic posture,

said to lack the qualities that inspire awe and fear: large size, majestic posture,

splendor from ornamental decoration and perfected beauty, devoid of human

splendor from ornamental decoration and perfected beauty, devoid of human

warmth. Instead, they embody friendliness, geniality and approachability, and

warmth. Instead, they embody friendliness, geniality and approachability, and

always a merciful smile. At the same time, they uphold an air of elegance and

always a merciful smile. At the same time, they uphold an air of elegance and

dignity as objects of religious worship. They are delightfully beautiful despite

dignity as objects of religious worship. They are delightfully beautiful despite

their lack of decoration, and instill their own quiet wonder by emanating human

their lack of decoration, and instill their own quiet wonder by emanating human

tenderness.

tenderness.

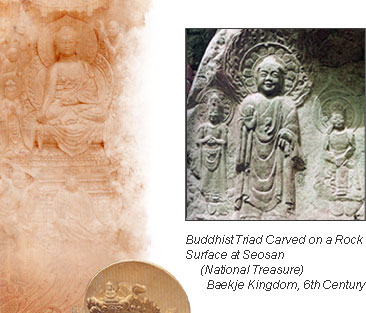

This Buddhist triad clearly displays the distinctive features of Korean Buddha This Buddhist triad clearly displays the distinctive features of Korean Buddha

images produced during the Three Kingdoms Period. Carved on the surface

images produced during the Three Kingdoms Period. Carved on the surface

of a rock cliff, as its name suggests, the three Buddha figures exhibit round,

of a rock cliff, as its name suggests, the three Buddha figures exhibit round,

plump faces with broad smiles that represent divine mercy and liberation from

plump faces with broad smiles that represent divine mercy and liberation from

all worries or cares. This smile, rarely seen on any other Buddha images the

all worries or cares. This smile, rarely seen on any other Buddha images the

world over, is widely referred to as ‘the smile of Baekje.’ The gently curved

world over, is widely referred to as ‘the smile of Baekje.’ The gently curved

lines flowing freely downward, the intimate figurative forms, and the warm smiles makes this triad more like

lines flowing freely downward, the intimate figurative forms, and the warm smiles makes this triad more like

human beings with flesh and blood than just religious icons.

human beings with flesh and blood than just religious icons.

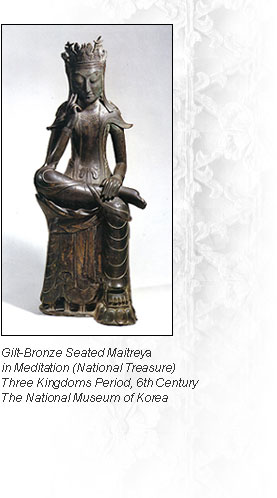

The images of Buddha in the ‘lotus meditation pose,’ in which The images of Buddha in the ‘lotus meditation pose,’ in which

he sits with one leg upon the other, his right elbow resting on his

he sits with one leg upon the other, his right elbow resting on his

right knee, his left hand on his right ankle and his head slightly

right knee, his left hand on his right ankle and his head slightly

inclined, suggesting contemplation, with his index and middle

inclined, suggesting contemplation, with his index and middle

fingers of his right hand gently touching his face, were in vogue

fingers of his right hand gently touching his face, were in vogue

during the Three Kingdoms Period. In fact, they are regarded as

during the Three Kingdoms Period. In fact, they are regarded as

the most beautiful of all the Buddha statues in this position ever the most beautiful of all the Buddha statues in this position ever

made in the world. This posture is believed to emulate the position

made in the world. This posture is believed to emulate the position

of Sakyamuni, historic Buddha, when he, as an Indian prince,

of Sakyamuni, historic Buddha, when he, as an Indian prince,

contemplated human suffering. After Buddhism was brought to

contemplated human suffering. After Buddhism was brought to

Korea from China, the stance eventually became artistically more

Korea from China, the stance eventually became artistically more

refined, to how we see it today. The image of Sakyamuni before

refined, to how we see it today. The image of Sakyamuni before

leaving the court to become a Seeker greatly inspired the imaginations

leaving the court to become a Seeker greatly inspired the imaginations

of the Korean people during the Three Kingdoms Period, particularly

of the Korean people during the Three Kingdoms Period, particularly

during the time when the worship of Maitreya (or Mireukbul in Korean),

during the time when the worship of Maitreya (or Mireukbul in Korean),

the Buddha of the Future, was at its peak. From the meditative

the Buddha of the Future, was at its peak. From the meditative

posture of the prince, they saw Maitreya, whom they believed

posture of the prince, they saw Maitreya, whom they believed

would save human beings from all suffering, and hence began

would save human beings from all suffering, and hence began

to make his icons in such a position.

to make his icons in such a position.

This gilt-bronze Maitreya, one of Korea’s most famous This gilt-bronze Maitreya, one of Korea’s most famous

Buddha statues in the ‘lotus meditation pose,’ has fascinated

Buddha statues in the ‘lotus meditation pose,’ has fascinated

people with his mysterious smile representing enlightenment.

people with his mysterious smile representing enlightenment.

The figure, with his head slightly inclined, the gentle smile on his face and the contented, serene

The figure, with his head slightly inclined, the gentle smile on his face and the contented, serene

pose with sleek lines running from his shoulders to his feet, epitomizes the mercy and tenderness

pose with sleek lines running from his shoulders to his feet, epitomizes the mercy and tenderness

of Lord Buddha. The warm facial expression amalgamated with the elegant body form and rhythmic lines reveals

the superior skill of the artist, who successfully captures the beauty of spiritual and mystical purity.

View the master's works

|