Thirdly,

the technique of underglazing with copper-paint in order to tint the celadon

ceramic red was attained by Thirdly,

the technique of underglazing with copper-paint in order to tint the celadon

ceramic red was attained by

Goryeo potters

for the first time in the world. To create such an enhancement of beauty,

patterns are drawn on the Goryeo potters

for the first time in the world. To create such an enhancement of beauty,

patterns are drawn on the

ceramic

using copper-based paint before applying the glaze. After being fired

at 1300˚C, the copper drawings turn ceramic

using copper-based paint before applying the glaze. After being fired

at 1300˚C, the copper drawings turn

bright

red through the process of oxidation. This was the most elaborate and

beautiful coloring technique that had been bright

red through the process of oxidation. This was the most elaborate and

beautiful coloring technique that had been

invented

in the history of ceramic crafts. Potters from Goryeo refrained from abusing

this technique, however, and only used invented

in the history of ceramic crafts. Potters from Goryeo refrained from abusing

this technique, however, and only used

it minimally

to accentuate the harmony of different colors within the ceramic. Chinese

potters were not able to develop it minimally

to accentuate the harmony of different colors within the ceramic. Chinese

potters were not able to develop

the system

to apply underglazing with copper-paint until the 14th century, 200 years

after Goryeo ceramic craftsmen. the system

to apply underglazing with copper-paint until the 14th century, 200 years

after Goryeo ceramic craftsmen.

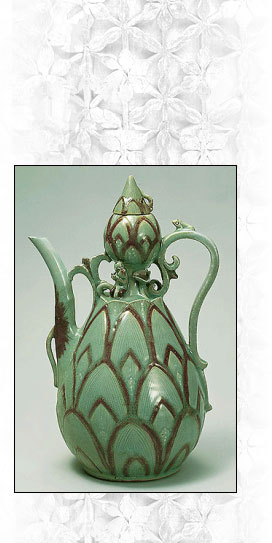

Gourd-shaped

Celadon Ewer Underglazed with Copper Red Gourd-shaped

Celadon Ewer Underglazed with Copper Red

Goryeo,

13th Century Goryeo,

13th Century

32.5cm

in height and 16.8cm in diameter at its widest point 32.5cm

in height and 16.8cm in diameter at its widest point

The

abundant use of bright red copper underglazing on this The

abundant use of bright red copper underglazing on this

unique

celadon ewer coexists perfectly with the color of blue unique

celadon ewer coexists perfectly with the color of blue

sky

after a rainstorm during an autumn afternoon. The body sky

after a rainstorm during an autumn afternoon. The body

is

shaped like a gourd with two lotus flowers of different sizes is

shaped like a gourd with two lotus flowers of different sizes

on

top of each other. The flower on the lower body is slightly on

top of each other. The flower on the lower body is slightly

opened

in the shape of a pond from which flower stems grow. opened

in the shape of a pond from which flower stems grow.

A boy

sits on the neck holding a lotus bud in his hand dipping A boy

sits on the neck holding a lotus bud in his hand dipping

his

feet into the pond while a small frog is poised to jump from his

feet into the pond while a small frog is poised to jump from

the

handle, exemplifying vivid evidence of the Goryeo people’s the

handle, exemplifying vivid evidence of the Goryeo people’s

deep

love of nature and rich imagination. The veins of each petal deep

love of nature and rich imagination. The veins of each petal

are

delicately incised with copper-red outlines and occasional white are

delicately incised with copper-red outlines and occasional white

dots

serving to further enliven the overall effect of subtle luxuriousness. dots

serving to further enliven the overall effect of subtle luxuriousness.

These achievements made great contributions to the development

of the ceramic crafts and arts in Korea and the world.

Some critics profoundly say that they also helped Goryeo celadon ceramic art move

one step closer to art’s divine function of

“purifying human minds with the power of beauty.” A great poet of the Goryeo Dynasty,

Yi Gyu-bo, said that Goryeo celadon is

made “by borrowing the magical power of heaven,” while his Chinese contemporaries praised

it with expressions such as,

“number one under heaven” and “extreme beauty.” Even today, many connoisseurs reveal their

admiration of Goryeo celadon

works by calling them “blessings of heaven” perfected by “God’s hands.”

The production of celadon ceramic art work that gave birth

to this splendid world of beauty entered a period of steady

decline paralleling the political and social turmoil during the late Goryeo Dynasty until

it gradually disappeared from the

ceramics sphere in Korea, making way for a new type of earthenware: Joseon Dynasty white

porcelain. Sadly, the world had

been deprived

of the mysterious beauty of celadon for some 600 years until the vision

of one man came to be. been deprived

of the mysterious beauty of celadon for some 600 years until the vision

of one man came to be.

Cho

Ki-jung, master celadon potter, was once a student of law who dreamt

of becoming a leader of the Cho

Ki-jung, master celadon potter, was once a student of law who dreamt

of becoming a leader of the

nation’s

judicial branch. His interest in ceramic crafts first began when he was a

student at the Resources nation’s

judicial branch. His interest in ceramic crafts first began when he was a

student at the Resources

Research

Association, studying how Korea, a poor agricultural country, could

promote economic Research

Association, studying how Korea, a poor agricultural country, could

promote economic

development

by overcoming a lack of natural resources. He traveled to different

parts of the country to development

by overcoming a lack of natural resources. He traveled to different

parts of the country to

look

for potential resources for his research. This is when he came across

countless kiln sites filled look

for potential resources for his research. This is when he came across

countless kiln sites filled

with

broken pieces of ceramic art work hidden in various mountainsides. His discovery

revealed that with

broken pieces of ceramic art work hidden in various mountainsides. His discovery

revealed that

there was something

in Jeollanam province that had promoted the development of ceramic art works there was something

in Jeollanam province that had promoted the development of ceramic art works

yet left kilns and

ceramic pieces behind. He was particularly attracted to the kilns

in the town of Gangjin, yet left kilns and

ceramic pieces behind. He was particularly attracted to the kilns

in the town of Gangjin,

known

as the home of Goryeo celadon. Fascinated with the glorious past of

celadon that disappeared known

as the home of Goryeo celadon. Fascinated with the glorious past of

celadon that disappeared

into

history along with the Goryeo Dynasty, Cho decided that he would revive

the wonders of this lost history. into

history along with the Goryeo Dynasty, Cho decided that he would revive

the wonders of this lost history.

However,

because celadon making techniques were not left on record and were essentially

extinct, he However,

because celadon making techniques were not left on record and were essentially

extinct, he

had

to train himself in this specialized art, mainly through experimentation.

He first focused on the earth from had

to train himself in this specialized art, mainly through experimentation.

He first focused on the earth from

which

ceramic art work is made. He used different combinations of silica, feldspar,

limestone, terra alba, which

ceramic art work is made. He used different combinations of silica, feldspar,

limestone, terra alba,

and clay (the

most common elements of ceramic) in his experiments and ceramic

art works. and clay (the

most common elements of ceramic) in his experiments and ceramic

art works.

He

then combed through the mountains of Korea to look for high-quality

ingredients. He fetched earth and stones He

then combed through the mountains of Korea to look for high-quality

ingredients. He fetched earth and stones

of

extraordinary qualities from all across the nation. It is said that

he wandered over a mountain for 15 days in search of

extraordinary qualities from all across the nation. It is said that

he wandered over a mountain for 15 days in search

for rocks

that could be used for the iron-paint underglaze, during which he slept

on dirt and ate dried breadcrumbs. His efforts were not in vain, though,

and Cho was able to create an iron-painted ceramic art piece. for rocks

that could be used for the iron-paint underglaze, during which he slept

on dirt and ate dried breadcrumbs. His efforts were not in vain, though,

and Cho was able to create an iron-painted ceramic art piece.

View the master's

works |