While

he was pursuing the dream of recreating Goryeo celadon, Cho came across

a researcher from While

he was pursuing the dream of recreating Goryeo celadon, Cho came across

a researcher from

a porcelain company

based in Gwangju. He shared his knowledge of high-quality earth and stones

with a porcelain company

based in Gwangju. He shared his knowledge of high-quality earth and stones

with

the company, and

he was invited to participate as a visiting researcher in the laboratory.

Here he was the company, and

he was invited to participate as a visiting researcher in the laboratory.

Here he was

able to put forth his

ideas of experimentation with all imaginable combinations of different

components. able to put forth his

ideas of experimentation with all imaginable combinations of different

components.

He

became more familiar with the different properties of minerals used in

ceramics through his He

became more familiar with the different properties of minerals used in

ceramics through his

thorough

studies and repeated tests. The knowledge he gained from this experience

became the thorough

studies and repeated tests. The knowledge he gained from this experience

became the

basis

for Cho’s later work in recreating Goryeo celadon. basis

for Cho’s later work in recreating Goryeo celadon.

In

1963, he discovered a small portion of celadon glaze at a kiln

site of from the Goryeo Dynasty. In

1963, he discovered a small portion of celadon glaze at a kiln

site of from the Goryeo Dynasty.

A

thorough study of earth and broken celadon pieces from a number of kilns

resulted in the finding A

thorough study of earth and broken celadon pieces from a number of kilns

resulted in the finding

of

a unique mineral not found anywhere else. It was revealed that the mysterious

substance that of

a unique mineral not found anywhere else. It was revealed that the mysterious

substance that

gave

Goryeo celadon its heavenly color was not a mystery after all; the key

to the quest was a cockle gave

Goryeo celadon its heavenly color was not a mystery after all; the key

to the quest was a cockle

shell

commonly seen at the seaside. Cho found a mixture of clay and crushed

cockleshell in the corner shell

commonly seen at the seaside. Cho found a mixture of clay and crushed

cockleshell in the corner

of

one kiln site. of

one kiln site.

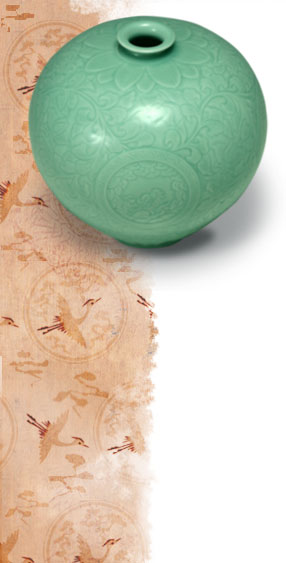

Cho put his new finding into practice by making

the glaze with powdered shell. He fired one ceramic piece

after another, varying the kiln temperature and thickness of the glaze.

One morning, Cho held up one of his

finished works from the kiln against the morning sunlight when he saw

a piece of heaven, the color

that he was looking for throughout his life as a potter. He held it up

high and ran

out shouting elatedly, “It’s a celadon, true celadon!” as the joyous emotion

filled

his heart.

In 1966, Cho’s regeneration of Goryeo celadon

and its superb color was

approved and praised by a renowned art historian from the National Museum

of Korea, Choe Sun-woo, who encouraged Cho to continue with his pursuit

of

perfection. These words of support and encouragement became the driving

force for Cho’s continued effort to realize his dream.

After his celadon glaze was celebrated by the

public, he built his own kiln

and named it “Mudeungyo,” or, “The Kiln of Mudeung Mountain.”

Cho continued his pursuit of recreating Goryeo celadon while he became

a

renowned

potter in international circles by participating in the Osaka International renowned

potter in international circles by participating in the Osaka International

Exhibition

and Dallas World Expo. His celadon works have been sold in Europe, Japan,

and the U.S. since 1973. Exhibition

and Dallas World Expo. His celadon works have been sold in Europe, Japan,

and the U.S. since 1973.

Cho

was not satisfied by mere momentary fame, however, and continued

to strive to realize the form of perfection in Cho

was not satisfied by mere momentary fame, however, and continued

to strive to realize the form of perfection in

Goryeo

celadon. The discovery of a 12th-century celadon kiln site in 1973 by

a research team from the National Goryeo

celadon. The discovery of a 12th-century celadon kiln site in 1973 by

a research team from the National

Museum

of Korea gave Cho the real answer. The broken celadon ceramic pieces from

the Gangjin site were evidence Museum

of Korea gave Cho the real answer. The broken celadon ceramic pieces from

the Gangjin site were evidence

that

this was where the best of Goryeo celadon was once made. In 1977, Cho

lead the Celadon Recreation Committee to that

this was where the best of Goryeo celadon was once made. In 1977, Cho

lead the Celadon Recreation Committee to

build

a new kiln in Gangjin based on the knowledge and experience gained from

the excavation of hundreds of kiln sites. build

a new kiln in Gangjin based on the knowledge and experience gained from

the excavation of hundreds of kiln sites.

On

December 27, 1977, the fire of the Goryeo Celadon kiln in Gangjin

was lit once again after 600 years of On

December 27, 1977, the fire of the Goryeo Celadon kiln in Gangjin

was lit once again after 600 years of

abandonment.

The nation’s eyes were turned to this small town, and the people’s hearts

beat as one in excitement abandonment.

The nation’s eyes were turned to this small town, and the people’s hearts

beat as one in excitement

with

those of the potters. The door of the kiln surrounded by hundreds of eager

spectators was opened on with

those of the potters. The door of the kiln surrounded by hundreds of eager

spectators was opened on

February

3, 1978, and the celadon pieces revealed themselves in divine light one

after another. The color of the February

3, 1978, and the celadon pieces revealed themselves in divine light one

after another. The color of the

sky,

the mysterious heavenly color from the legend, was recreated on earth.

One would have been good enough, sky,

the mysterious heavenly color from the legend, was recreated on earth.

One would have been good enough,

but

32 out of the 200 works fired inside the kiln came out as perfect resurrections

of Goryeo celadon. but

32 out of the 200 works fired inside the kiln came out as perfect resurrections

of Goryeo celadon.

Potters

of today came in contact with their ancestors from almost a millennium

ago through the successful rebirth Potters

of today came in contact with their ancestors from almost a millennium

ago through the successful rebirth

of

Goryeo celadon. The history of celadon ware in Korea was restored by Cho

Ki-jung, who devoted his life to of

Goryeo celadon. The history of celadon ware in Korea was restored by Cho

Ki-jung, who devoted his life to

finding

the secret behind the color of peace and serenity for the human soul.

Cho Ki-jung not only successfully finding

the secret behind the color of peace and serenity for the human soul.

Cho Ki-jung not only successfully

recreated

the world’s most beautiful ceramic ware but also opened a new page in

the history of ceramics by recreated

the world’s most beautiful ceramic ware but also opened a new page in

the history of ceramics by

continuing

the spirit of true craftsmanship that was lost for nearly one thousand

years. continuing

the spirit of true craftsmanship that was lost for nearly one thousand

years.

View the master's works |