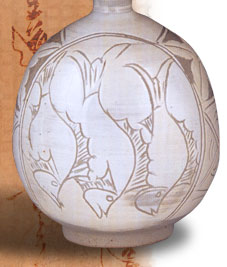

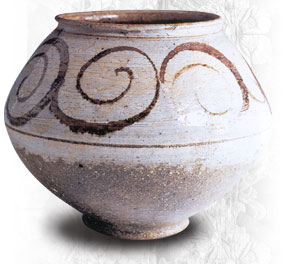

subsequently, cheap mass-produced Japanese porcelain began to flood the kingdom. The breathtaking natural beauty of Joseon earthenware, the serene image of a solitary moon shining softly over a gentle hill, that had fascinated Joseon people for several hundred years gradually faded away along with the fated dynasty. Seeing the tragic end of the era and Joseon white porcelain, Kim Un-hi came back to his birthplace as a poor, frustrated artisan who lost his honorary title of Master Potter of Gwanyo (‘government-operated kiln’). Thankfully, however, his return gave his hometown a new opportunity to reflect on its years as the center of Joseon ceramics. The works he made during this period for the masses displayed outstanding features that one can only expect from a leading gwanyo potter, in which artistic imagination is interlaced with practicality to create dynamism and freedom of expression. In the following decades, however, Kim’s family suffered from a huge drop in demand for traditional ceramic ware, a phenomenon caused by the arrival of cheap galvanized iron ware and plastic goods. The thriving ceramic workshops of Mungyeong began to close one after another, until only the Kim’s was left. Ironically, what helped Kim keep the family business going were the Japanese tourists who flocked to Korea following the 1965 summit talk between the two countries. These Japanese tourists arrived in droves at his tiny workshop hidden in a remote valley, and were amazed by what they believed was an incarnation of Ido Chawan, one of their most admired national treasures. Ido Chawan (or Jeongho Dawan in Korean) is a rustic tea bowl Japanese soldiers found during the Imjin Waeran (The War of the Ceramics) in the Joseon Dynasty. The tea bowl was later possessed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, one of the most powerful feudal lords in Japanese history. He was so amazed by its graceful beauty that he only used it for special ceremonious meetings with powerful warlords. Since then, a number of Ido Chawan have been designated as national treasures across Japan, including one, it is said, that its owner would not sell even for the Osaka Castle, home of Hideyoshi himself. Opinions vary, even among well-informed scholars, as to the origins and purpose of the wonderful ceramic called Ido Chawan. Some say that it was used as a rice bowl by Buddhist monks, while others argue that it had a religious function. Still, many others insist that it was a tea bowl. Whatever its use, Kim Jeong-ok is a descendent of the brilliant Joseon potter who created this and many other magnificent works of art. Born as the third son of Kim Gyo-su, Kim Jeong-ok learned how to use clay and the potter’s wheel at a young age under his father’s tutelage. When he was 18, he decided to continue the family tradition and work with clay for the rest of his life. People praised his pieces and said that his father, a master potter, had taught him well. However, following his father’s death when Kim Jeong-ok was only 32 years old, business dwindled as both his Korean and Japanese customers suddenly stopped visiting the workshop. A time of discouragement and frustration ensued, after which he opened a new workshop at the side of a road in Mungyeong, hoping that traffic and increased exposure would help bring back customers. By this time, he made everything he could to eke out a living, from tea bowls and buncheong ware, to white porcelain and even fancy flowerpots. But his time of difficulty continued, and he realized that he needed to win prizes in national craft competitions to gain a similar reputation as his father’s. With high hopes and lofty expectations, he entered a tea bowl and a buncheong jar into the 1986 National Folk Craft Show, but unfortunately they did not gain any interest from the critics View the master's works |

|||||||||||||

|